On entering the shop of James W. Queen & Co. at 924 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, a customer in need of a microscope may have felt overwhelmed by their choices. Founded in 1853, James W. Queen & Co., retailer and manufacturer of scientific instruments of all kinds, stocked simple microscopes (little more than magnifying glasses), compound microscopes, including monocular and binocular instruments, and microscope accessories made by American, English, French and German manufacturers. Customers could choose among watchmaker’s glasses, simple flower microscopes, linen provers (“for counting the threads in linen fabrics”), school and student’s microscopes, dissecting microscopes, portable travelling microscopes, family microscopes and clinical microscopes.

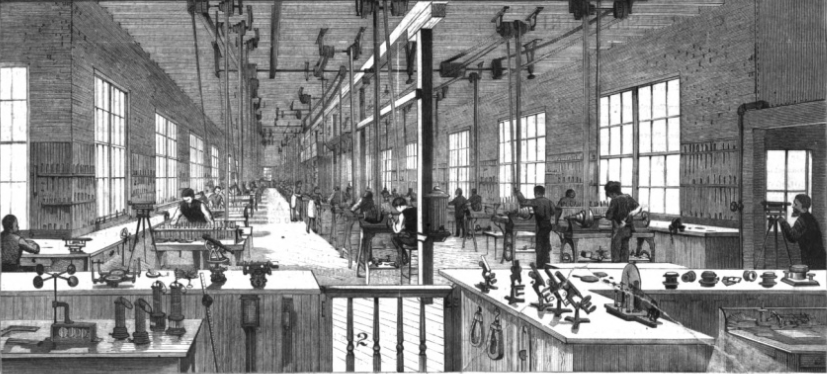

The instrument of the customer’s choice could then be fitted with technical accessories ranging from turn-tables for making specimen slides to watered dissecting troughs and polarising prisms for mineralogical analyses. In 1888, the Scientific American praised James W. Queen & Co. as the “largest and most comprehensive [business] of its kind in the United States or the world.” Their production of scientific instruments had “reached proportions which can hardly be appreciated without a visit to the shops.” Still, the Scientific American tried to recreate the experience of visiting James W. Queen & Co. by walking its readers through the different steps of making scientific instruments. The front page of the journal was covered with illustrations of the various departments at James W. Queen & Co.: The company had its own brass foundry, machinery for grinding lenses and spacious, bright rooms for its designers.

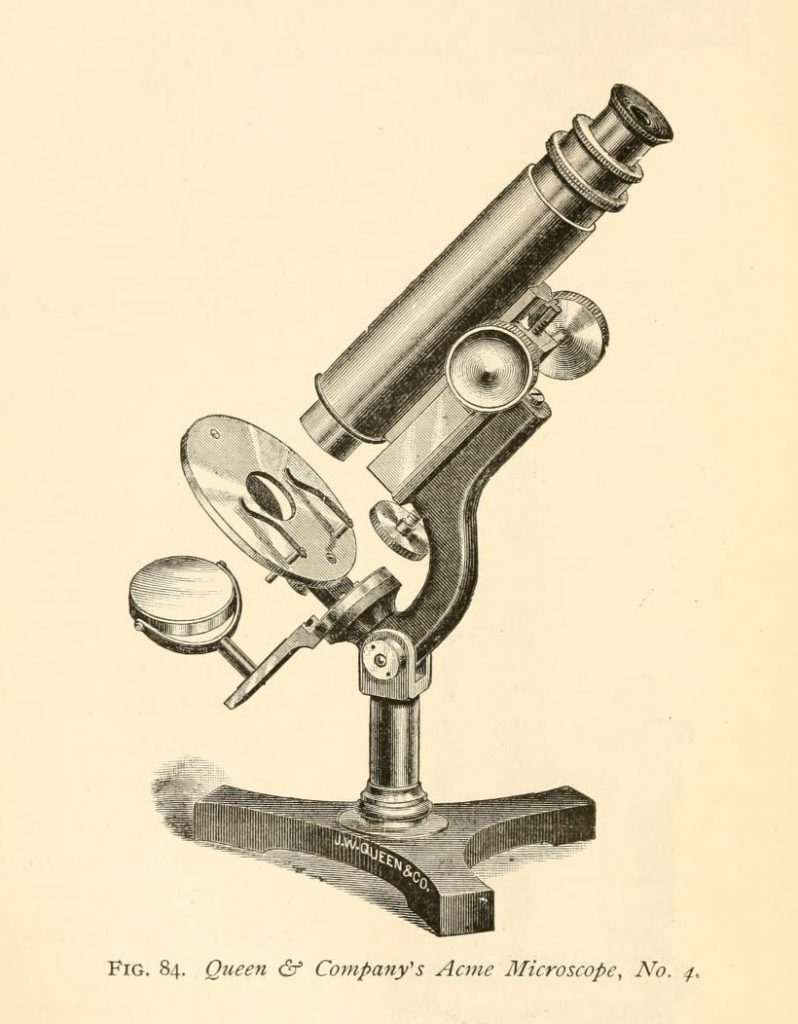

It is unclear if James W. Queen & Co. produced most (or some) parts of their microscopes themselves or if they merely reassembled pieces of instruments produced by other manufacturers. Whatever James W. Queen & Co. did, they did it very successfully. One of the best customers of the company was the US government. The US Army Medical Museum, the Bureau of Animal Industry and the Department of Agriculture were just some of the US departments that relied on microscopes for their daily work. When the article on James W. Queen & Co. was published in the Scientific American, the government had just ordered several Acme microscopes, a series of inexpensive instruments produced by James W. Queen & Co. since 1881. Two years later, Thomas Taylor, official microscopist of the Department of Agriculture, used his Acme microscope to exhibit tea leaves and an embryo tapeworm at the Annual Soirée of the Washington Microscopical Society. Microscopy soirées like this – exhibitions of the latest microscopes, specimen slides carefully prepared for the occasion, or stunning photomicrographs – were often more entertaining than strictly educational. Apparently, governmental microscopical work could also be entertaining. The soirée drew 500 visitors, many of whom “called forth exclamations of delight and wonder.”

While making microscopes was a difficult task in itself, advertising them was another hurdle microscope manufacturers faced. In addition to circulating regular trade catalogues listing products and prices, James W. Queen & Co. issued a publication that was half trade catalogue and half scientific journal. The Microscopical Bulletin and Optician’s Circular, later The Microscopical Bulletin and Science News, was published from 1883 to 1902 and ingeniously combined price lists, adverts and microscopical news from the US and abroad. Moreover, the wry comments occasionally inserted by the editor, Edward Pennock, made the bulletin a remarkably good read for a trade catalogue turned scientific journal. In 1882, a correspondent of the bulletin enquired: “I want to know if you have a glass that I can see through paper or leather, and if you have one, please to be kind enough to send me the price of it at once.” “Punch a hole in the paper or leather,” Pennock replied.

Since the bulletin was digitised by Google and is not included in the Biodiversity Heritage Library, it will not be uploaded to Worlds of Wonder. Still, it is a delight to read and you can do so in the HathiTrust library.

Further reading

Padgitt, D. L. (1975). A Short History of the Early American Microscopes. London and Chicago: Microscope Publications Ltd. http://www.mccroneinstitute.org/uploads/A_Short_History_Early_American_Microscopes.pdf