Microscopy illustrations made by the English naturalist Philip Henry Gosse (1810-1888) travelled far and wide in the late nineteenth century. With his father an impoverished gentleman trying to make a living off of miniature painting, Gosse had picked up the drawing of plants and animals when he was only a boy. He became a prolific science writer and illustrator, and his illustrations were often copied and reproduced in books and journals. Thanks to the work of our Worlds of Wonder contributors, we are beginning to see which of his illustrations were copied and by whom, and where they travelled.

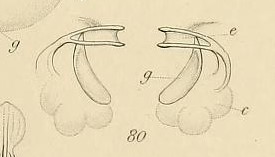

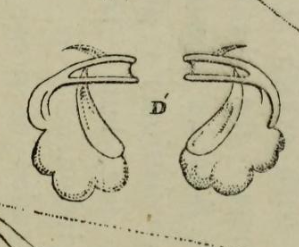

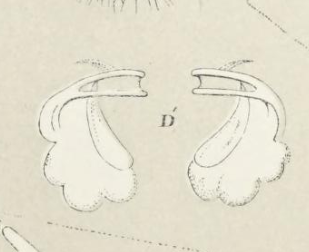

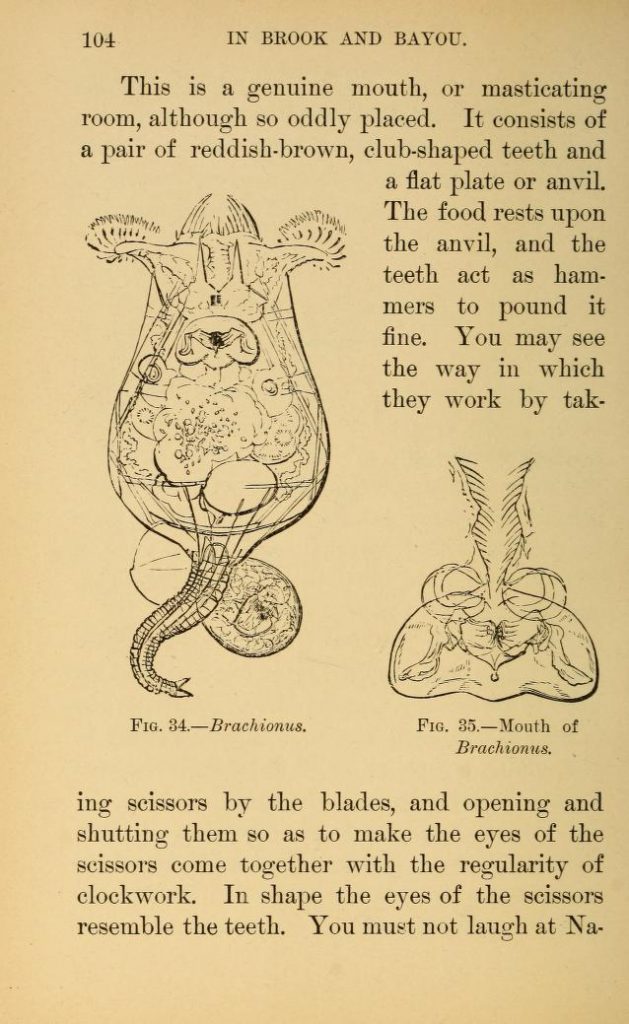

Both Henry James Slack’s Marvels of Pond-Life (1861) and Mary Ward’s Microscope Teachings (1866) copied one of Gosse’s illustrations. They included a drawing of the jaw of a rotifer, a microscopic freshwater animal, which Gosse had made in 1862. Marvels of Pond-Life (1861) introduced beginners in microscopy to freshwater plants and animals, with each chapter focusing on one month of the year when the reader was likely to find the specimen described. Most of the illustrations in the book were made by Charlotte Mary Slack, Henry James Slack’s wife, who combined Gosse’s illustration with drawings of her own. The resulting plate later reappeared in Ward’s Microscope Teachings (1866).

Gosse’s illustration of a rotifer jaw in his 1862 paper…

…in Mary Ward’s Microscope Teachings (1866)…

…and in Henry James Slack’s Marvels of Pond-Life (1861)

Mary Ward (1827-1869) was born into an Anglo-Irish aristocratic family. She did not receive a formal scientific education, but she dedicated much of her time to making microscopic observations, describing and illustrating them. As a young girl, she occasionally bound her descriptions and illustrations of microscopic specimens into little books and passed them on to friends and family. Later, she revised and published some of her works on microscopy. Microscope Teachings (1866) was one of her most successful publications.

Philip Henry Gosse had stressed the importance of field trips for the microscopist, instructing his readers to procure specimens from local ponds or the sea shore. Mary Ward, however, emphasised the domestic side of microscopy, showing her readers how to repurpose things at hand to make microscopic observations. She explained that she “removed the microscope tube from the stand, and mounted it . . . upon a cushion raised on a large book, so that [she] could look as through a telescope into the wine-glass” where she kept microscopic animals. Thus, Ward’s book not only copied Gosse’s illustration but framed it quite differently, as resulting from observations made with the help of household items.

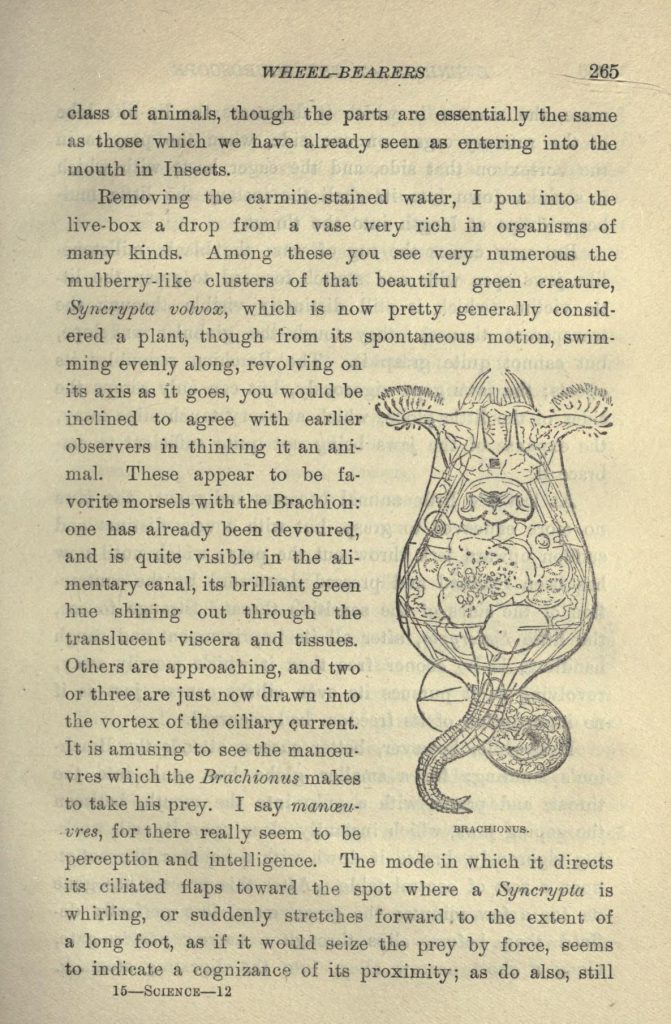

Gosse’s illustration of a rotifer in his Evenings at the Microscope (1859)…

…and in Clara Kern Bayliss’s In Brook and Bayou (1897)

Meanwhile, the illustrations published in Gosse’s popular Evenings at the Microscope (1859) travelled to the United States, where they reappeared in a children’s book, Clara Kern Bayliss’s In Brook and Bayou (1897). Bayliss (1848-1948) was co-editor of the progressive journal The Child-Study Monthly, which advocated for child-centred pedagogy. She edited a section of the journal called the Educational Current, where she commented on developments in child education. Bayliss wrote several children’s books that often blurred the line between fact and fiction and gave ample room to her young readers’ imagination.

As Bayliss explained in the Educational Current of May, 1899, she regarded a child’s made-up stories as “fiction in its earliest and crudest form, poems and novels by untrained hands”. Instead of teaching children how and what to see through the microscope, Bayliss guided them through a microcosm inhabited by minute animals, mermaids, and a boy shrunk to microscopic size, who was himself microscopically examined by microorganisms. Thus, in Bayliss’s book, Gosse’s illustrations no longer testified to the author’s ability to make truthful scientific observations. Instead, they became an invitation to explore a spectacular, often fictive, microscopic world and to train the imagination rather than the eye.