The crowdsourced Worlds of Wonder data have been published open access on DataverseNL, an online data repository used by Dutch universities. In preparing the data for publication, the Worlds of Wonder researchers received help from the data stewards at Maastricht University, as well as the Open Science Community Maastricht, to make sure that the data would comply with the FAIR guidelines for data reuse. In the interview below, one of the researchers, Lea Beiermann, talks about her experience of making data FAIR.

The interview originally appeared as part of a series on FAIR data in FASoS Weekly, the newsletter of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Maastricht University (UM).

How did you find out about FAIR?

The first time I heard about FAIR was in a presentation by Michel Dumontier (at UM’s Institute of Data Science, IDS). After that, I saw that the UM library actively promoted the FAIR principles on social media. I also knew about FAIR because it was an important element of the data management plan that I had to write to receive funding for my PhD research.

What does FAIR mean to you?

From the data science perspective, FAIR describes data that are findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. As stated on the IDS website, FAIR is a good foundation to make data science more responsible. Ideally, it allows data to be shared widely.

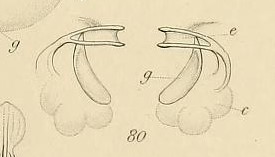

For me, however, FAIR also means responsible data collection practices. During my PhD research, I noticed that this is an additional challenge, and that ethically sound data collection is sometimes not easily compatible with FAIR principles. I ran a web-based citizen science project as part of my PhD, which asked citizen scientists to help me analyse historical sources. According to the FAIR principles, I should have made sure that the crowdsourced data is reusable, and to some extent I did manage to do that, but sometimes it was difficult to turn the historical research of my citizen scientists into machine-readable data.

From a data scientist’s point of view, I probably would have got the most (re)usable clean data by having citizen scientists make yes/no classifications and tick boxes – quite monotonous tasks. A large part of my project consisted of such classification tasks, but I think the more interesting research (from a historian’s point of view, and also more interesting for the citizen scientists) happened in discussions in our chat forum. Of course, I can still make these discussions findable and accessible, for example by storing them with appropriate metadata, but they cannot be reused as easily as the more simple, machine-readable data.

Why did you decide to make your data FAIR?

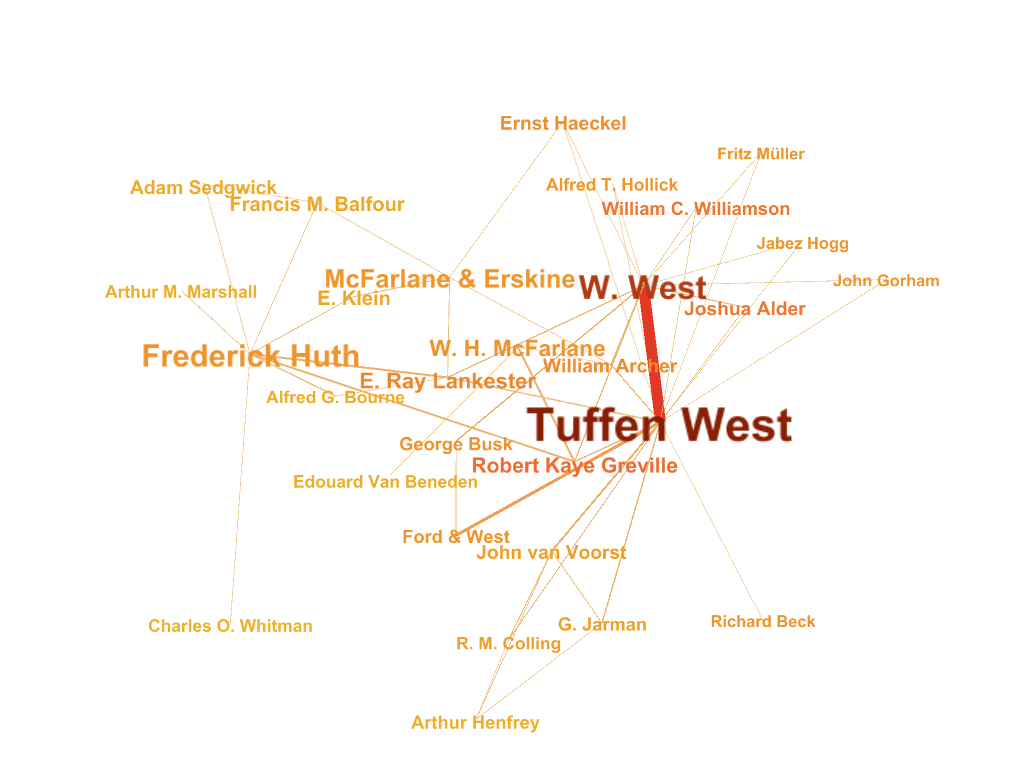

Fair use of data is widely considered the default for citizen science projects. The consensus is that data that are crowdsourced should not belong to the principal researchers only but to everyone who helped compile them or who would like to reuse them. I reused the data collected through another citizen science project “Science Gossip” and found them a useful addition to my own data. I wanted to make it possible for others to reuse our project data too, so that is mainly why I decided to make my data FAIR.

How has the data steward (Maria Vivas Romero) helped you make your data FAIR?

Maria helped me understand and fill out UM’s data management plan – and I learned much more about FAIR data when we filled out the plan. Maria reminded me of the important role of metadata, such as commonly used keywords in my field of research, and that I could even make data findable whose use is restricted by copyright. For example, I could not share photos of archival material, but I could add metadata on these sources to my project to let other researchers know that they exist.

Was it a lot of work to make your data FAIR?

I am actually still in the process of making my data FAIR, even though I started my PhD a while ago. It does take quite some time, but for me this is absolutely worth it. After all, I used data collected by others, so it seems only fair to try and make my data as accessible and reusable as I could. And Maria has been a great help in making that possible.

How do you think making data FAIR benefits you?

I think there are several benefits to making your data FAIR. First, besides that I think it is only fair to make data available to others because I also make use of other researchers’ data, it also make my research and me as a researcher more findable and visible. Second, making data FAIR means that other research projects can benefit from all the work citizen scientists put into my project, so it gives greater value to their (and my) work. Third, FAIR data reuse can generate new research ideas that I did not think of but that might be interesting for my work.

How do you think making data FAIR helps other researchers?

Other researchers may reuse the historical data we collected, as well as the Python scripts one of my citizen scientists, Peter Mason, wrote to analyse the data. This means that others cannot only reuse historical data but also, possibly, learn from the way we analysed our data and do it in a similar way, or better. They can also get a clearer idea of the kind of data citizen science projects yield. I expected to get much cleaner data than we actually gathered – seeing the data I work with now in advance would have helped me to have more realistic expectations.

What hurdles did you come across when trying to make data FAIR?

I think making data FAIR does require quite some time. What I personally also experienced as a hurdle, or rather time-consuming, was combining the richness of qualitative historical research with machine-readability, or simple keywords. Moreover, I know that many of my colleagues collect sensitive data that they cannot share. On the other hand, we do have an excellent data steward who is happy to help us overcome these hurdles!